By Aadityan Ganesh and Hari Ramasubramanian

The Indian Premier League (IPL) auctions have long been a spectacle of excitement, strategy, and intrigue. The sheer complexity of team-building, combined with the high stakes of player retention and acquisition, creates a dynamic where franchises vie to outbid each other while staying within their allocated budgets. As we approach the upcoming 2025 mega-auctions, significant changes have been introduced by the IPL Governing Council, particularly concerning player retention and the much-debated Right-to-Match (RTM) card.

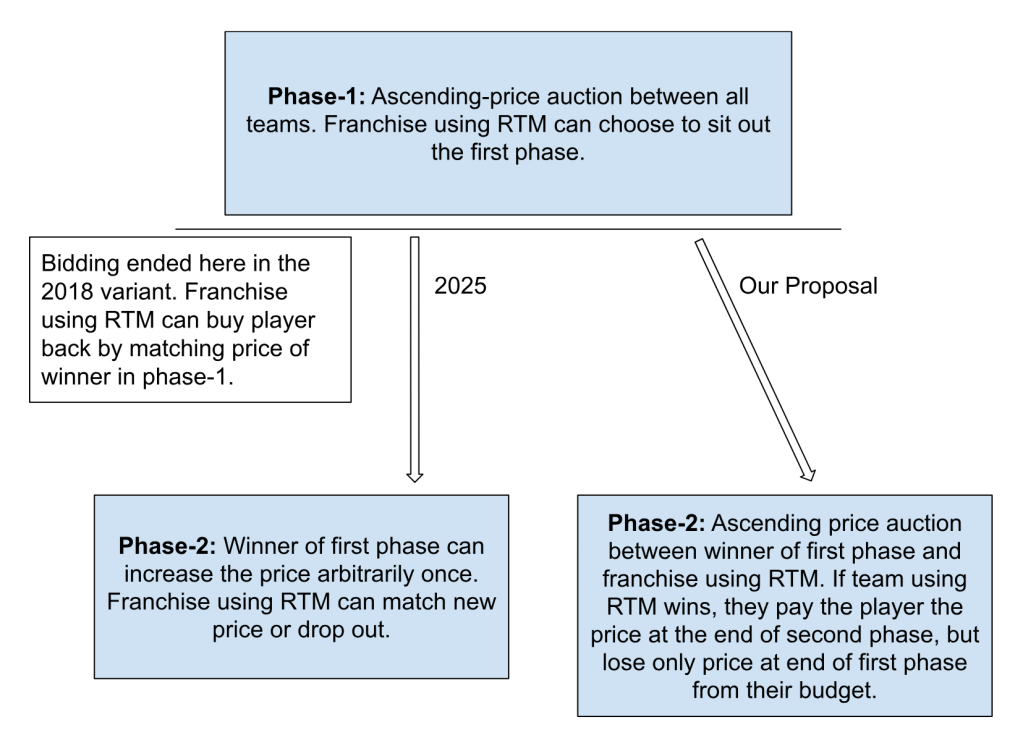

The RTM card is intended to allow franchises to buy their players back in the auction at a discounted price. In this article, we review the right-to-match rules announced by the IPL governing council and compare the new rules with our proposal from a previous post.

In this article, we critically analyze the new RTM rules, juxtapose them against the 2018 RTM variant, and introduce an alternative model which we believe offers a more equitable balance between competitive fairness and franchise budgeting. In doing so, we aim to foster a deeper discussion among academic researchers, cricket enthusiasts, and experts interested in auction design, strategic decision-making, and sports economics.

Understanding the RTM Mechanism: Evolution and Function

The RTM is designed to give franchises the opportunity to reacquire a player they have previously at a discount. This acts as a reward mechanism for teams to invest long-term in their players and not start afresh every time there is a mega-auction. However, providing a discount to teams naturally results in a lower selling price and a lower remuneration to players (more details can be found in our previous post). The evolution of the RTM mechanism reveals a continual tension between player compensation and a discount to teams for investing in future prospects.

The 2018 version of the RTM allows the franchise to sit the entire bidding process out and match the price at which the auction terminates. The upcoming 2025 version adds a more nuanced second phase on top of the 2018 variant: after the first phase (which also determines a “provisional winner”), if a franchise uses their RTM, the provisional winner from the first phase can raise their bid once. The team using the RTM can either match the new price or forfeit the player. In our proposal, we suggest a different second phase — instead of a one-time price hike, the auction should proceed in an ascending price format as in the first phase between the winner of the first phase and the franchise with the RTM. The player will be paid the price at which the second phase ends. However, if the team with the RTM wins, they will only lose the price at which the first phase ended from their budget.

To provide clarity, we use a running example involving Sunrisers Hyderabad (SRH) and Heinrich Klaasen. Suppose that Rajasthan Royals (RR) wins the first phase at 8 crores after Chennai Super Kings (CSK) drop out of the bidding. Assume RR’s valuation of Klaasen is ₹12 crores, while SRH values him at ₹14 crores. How would the three different RTM models play out?

- 2018 RTM Variant: SRH can use the RTM to match RR’s winning bid of ₹8 crores, thus buying Klaasen back at that price.

- 2025 RTM Variant: RR, having won the first phase, can choose to increase their bid once, say to ₹10 crores. SRH must then decide whether to match that price and pay ₹10 crores or forfeit the player to RR.

- Our Proposal: Instead of a one-time hike, RR and SRH would enter a second ascending-price bidding phase. If RR drops out at ₹12 crores, SRH pays that amount to Klaasen but loses only ₹8 crores, the price at which the first phase ended, from their auction budget.

The figure highlights the variations in outcomes for both franchises and players, particularly in terms of impact to their budget and player remuneration.

The Economics of Auction Design: A Detour into First-Price and Second-Price Auctions

To better understand the strategic implications of the RTM variants, we briefly explore first-price and second-price auctions. These concepts that are quite common in auction theory are relevant for assessing the strategic behavior of franchises during the auction.

- First-Price Auction: Imagine an auction where every bidder submits a sealed bid, and the highest bid wins. In this format, the winning bidder has to pay exactly what they bid. Let’s say a franchise believes a player is worth ₹10 crores to them, meaning they think the player can bring value equivalent to that amount. If they bid the full ₹10 crores and win, they effectively break even—they get a player worth ₹10 crores, but they also pay ₹10 crores, leaving no “profit” or surplus from the transaction.

This is why bidders often don’t bid their maximum valuation. Instead, they tend to “shade” their bids—offer a little less than what they believe the player is truly worth. For example, a team that values a player at ₹10 crores might bid ₹8 or ₹9 crores, hoping to win at a lower price and gain some surplus value. However, there’s a trade-off here: bidding too low increases the risk of losing the player to a higher bid. So in a first-price auction, teams must carefully balance the desire to pay less with the fear of losing the player altogether.

This strategic dilemma makes first-price auctions tricky. The key is guessing how much other teams are willing to pay and finding that sweet spot where your bid is high enough to win but low enough to ensure you’re not overpaying. Such strategizing turns out to be a non-trivial exercise, and in practice, it is observed that bidders typically shade their bids much less than what they optimally should. Thus, auctions that do not involve such strategizing, i.e, where bidders maximize their “profits” by bidding their values are preferable. We look at one such auction next.

- Second-Price Auction: Here, the highest bidder still wins, but instead of paying their own bid, they pay the second-highest bid. This seemingly small change has big strategic implications. In this case, there’s no need to shade your bid or play any guessing games. The winning team will always pay less than or equal to their maximum valuation because the price is determined by the second-highest bidder, not their own bid.

Let’s use the same example: a team values a player at ₹10 crores. In a second-price auction, they can confidently bid the full ₹10 crores because, even if they win, they’ll only pay what the second-highest team bid. So if the next highest bid was ₹8 crores, they’d get the player for ₹8 crores—even though they were willing to pay ₹10 crores. This format encourages teams to bid exactly what the player is worth to them, without worrying about overpaying.

By removing the incentive to shade bids, second-price auctions allow teams to focus on their own valuations, simplifying the decision-making process. The format is designed to ensure that the team who values the player the most wins, while still protecting them from paying more than necessary.

To appreciate the 2025 variant of the RTM, observe that it functions as a hybrid between these two auctions. In the second phase of the 2025 RTM, the highest bidder effectively engages in a first-price auction (they hike the price and pay whatever they hiked to if they end up winning), while the RTM-using franchise operates in a second-price format (they pay the bid of the winner from the first phase). This disparity creates strategic asymmetry, as one team faces pressure to underbid to optimize their utility, while the other can bid without having to worry about overpaying.

Comparing Discounts Across Various RTM Formats

To critically assess the discount provided by each RTM variant, we first define a benchmark — the counterfactual auction in which no RTMs exist. In this scenario, the team with the highest willingness-to-pay for a player must outbid all others to secure the player’s services. In our example, SRH would have to outbid RR and pay ₹12 crores, the point at which RR exits the auction. In other words, with no RTMs, the team willing to buy a player back must pay the second highest value.

The 2018 variant provides the largest discount from the benchmark amongst the three variants. In the 2018 version (and for that matter, in the other two variants too), the first phase ends when the price crosses the third-highest value (i.e, the second-highest value when the team with the highest value sits out). Thus, the team with the second-highest bid wins the first phase. Using an RTM card will allow the franchise to purchase the player at the third-highest value as opposed to the second-highest value from the counterfactual world. In the Klaasen example, remember that SRH will pay ₹8 crores in the 2018 RTM version, which equals the third-highest value, the value of CSK. In the counterfactual benchmark, they will end up paying ₹12 crores, the value of RR.

As briefly discussed above, the 2025 version is an interesting mix-and-match between the first-price and the second-price auction. The winner of the first phase faces a first-price auction in the second phase – they pay whatever they bid in the second phase if they end up winning. Thus, the winner of the first phase should bid below their value when behaving optimally. In contrast, the franchise using their RTM faces a second-price auction — they pay the bid of the second-highest bidder. Thus, they can bid exactly their value. By using their RTM, they will only have to pay the shaded bid of the second-highest value and not the second-highest value. Once again from the Klaasen example, RR has a value equal to ₹12 crores and suppose they choose to hike the price to ₹10 crores in the second phase after the first phase ends at ₹8 crores. SRH thus gets a discount equal to ₹12 crores (from the counterfactual benchmark) – ₹10 crores = ₹2 crores.

In our proposal, the franchise using the RTM will lose only the price at the end of the first phase from their budget. While they do not get a discount in terms of the payment they make to the player, they retain a higher capacity to spend on other players while building their team. Back to the Klaasen example, SRH will have to pay Klaasen ₹12 crores (the price at which RR will drop out), but will lose only ₹8 crores from their budget. They can spend the discount ₹12 crores – ₹8 crores = ₹4 crores on other players in the auction.

To summarize the discussion above, the franchise using an RTM gets the highest discount in the 2018 variant, followed by our proposal and then the 2025 version. In terms of player remuneration, our variant guarantees the highest pay to the players, followed by the 2025 version and then the 2018 variant (for a more detailed discussion on player remuneration, see our previous post). In the remainder of the article, we discuss other strategic implications of the 2025 version and our proposal.

Unintended Consequences of Fancy RTMs

First, we observe that the discount from using RTM in the 2025 version is extremely dependent on the order in which players are auctioned. The valuations teams have for a player are already dependent on the order in which players are sold, irrespective of the presence of RTMs. The 2025 variant only makes this dependence worse. For example, a seasoned pacer like Bhuvaneshwar Kumar will be valued much more by teams if there are no other exciting fast bowlers to follow. Given that there are no strong fast bowlers to come, the team winning the first phase will not want to shade their bid much since losing Bhuvi to SRH (the franchise that will be using their RTM) will mean the winner will go into the tournament with a good pacer short. Thus, the winner must bid their entire value, resulting in no discount to SRH when compared to the counterfactual benchmark.

Second, we discuss the impact of loss aversion — a common tendency observed in humans to subvert losses even at unjustifiable costs. In the 2025 variant, the winner of the first phase has “provisionally won” the player before losing them to the franchise using the RTM. By loss aversion, it is extremely likely that the winner of the first phase will end up bidding more than their optimal response. If their optimal response is bidding extremely close to their value, then loss aversion might result in them bidding above their value! A franchise could thus potentially pay a premium by using their RTM!

Our proposal easily handles the issues highlighted above since the franchise using the RTM loses only the first phase price from their budget, irrespective of the other team’s behaviour in the second phase. Additionally, the winner of the first phase does not have to make a single “rash” decision to increase the price in the second phase. The price increases smoothly in the ascending-price auction in the second phase. Further, since the format in the second phase is the same ascending-price format as in the first phase, the winner of the first phase also has a reduced feeling of “provisionally winning” the first phase. Such psychological tricks go a long way in reducing loss aversion.

Finally, we discuss another issue that exists in both, the 2025 variant and our proposal. Teams can strategically use the RTM to hike the prices of bargain buys, with no intention of buying. For example, suppose the first phase ends at 4 crores for Sam Curran with RCB winning the auction. PBKS can use their RTM to force the auction into the second phase. In the 2025 variant, RCB will have to guess PBKS’s value and increase their bid accordingly. PBKS can now happily step out of the auction having slashed more funds from RCB’s budget. Indeed, there is also a risk involved — if PBKS are not interested in buying Curran and RCB give up the right to increase the price, PBKS will have to buy Curran at ₹4 crores.

The above problem persists with our proposal too. A franchise can force the winner of the first round into the second phase only to hike the price for the other team. However, there is more uncertainty in using the RTM strategically in our proposal. The winner of the first phase can pull out at any point in the second phase, and thus, the franchise with the RTM will have to keep calibrating the other team’s value with each increase in price. This is in contrast with the 2025 variant where the winner of the first phase will have to increase the price by a large chunk as soon as the RTM is used. A higher uncertainty can reduce the risk appetite of the franchise with the RTM card, and thus, can mitigate the effect of such strategic use of RTMs. All said, the manipulation considered above still exists even in our proposal. We only increase the difficulty in using RTMs for such purposes.

We summarize the above discussions in the table below.

| 2025 Variant | Our Proposal |

| Discount from RTM is extremely dependent on the order in which players are sold. If the player being sold is extremely key (for example, the last seasoned pacer), the winner of the first phase will shade their bid not by much. Thus, the franchise using the RTM card does not get that large a discount. | The price increase in the second phase is irrelevant to the team using their RTM since they will only be slashed the price from the first phase from their budget. While the teams’ values for players depend non-trivially on the order in which they are sold, our RTM proposal does not accentuate this dependence. |

| Loss aversion can cause a smaller discount to the team using the RTM. The team winning the first phase might not shade its bid as aggressively as it should if it behaves optimally. | Effects of loss aversion are felt only in the second phase. The franchise using the RTM card is slashed only the price at the end of the first phase from their budget. Thus, the actions taken by the winner of the first phase is not extremely important to the discount for the team using the RTM. |

| Teams can strategically use the RTM card to inflate the price of other teams. For example, a franchise can choose to match the winner’s bid and back out as soon as the team bumps up the price. | While a similar issue exists, we believe the effects of such issues are controlled better than the 2025 variant. A smooth increase in prices imply that the franchise strategizing with their RTM will have to reconsider at the end of every smooth increase in prices — thus increasing uncertainty. |

In conclusion, while the IPL Governing Council’s modifications to the RTM mechanism reflects a well-intentioned effort to balance player compensation and discounts to teams for investing in their players, they introduce a host of unintended consequences that could undermine the fairness of the auction. Our proposed alternative seeks to address these concerns by ensuring a more balanced second phase that provides a higher budgetary flexibility while simultaneously maintaining competitive fairness.

However, it is clear that the design of efficient auctions that ensure fairness for all parties—players, franchises, and the league itself—remains an open challenge. We hope that this discussion will spark further debate and exploration among researchers, sports economists, and cricket analysts. Our proposal, while a step in the right direction, is just the beginning of this broader conversation.